eyckgalleryartistsexhibitionsnewspublications

eyckgalleryartistsexhibitionsnewspublications

Tobia Bezzola

Models, Possibilities:

Thomas Struth’s “Nature & Politics”

“Nature & Politics” is the title Thomas Struth has chosen for the highly concentrated exhibition of his work from the past decade. What might be encompassed under this title? At first sight, the label “nature” is not that problematic. There are an infinite number of forms of nature, of natura naturata, that can be represented, and this is indeed something photographers have done ever since photography was invented. However, one swiftly realizes that what Struth has in mind are not landscape images in the conventional sense.

It is less evident whether and how you can show images of “politics”. Its institutions take material form as architecture and that can be photographed. And of course one can also portray the people active in politics. But it is equally clear that in such images “politics” per se is not visible. In the case of a reflective artist such as Thomas Struth we can therefore assume that he understands the title “Nature & Politics” at a more fundamental level and that his work of recent years consciously seeks to dig deeper.

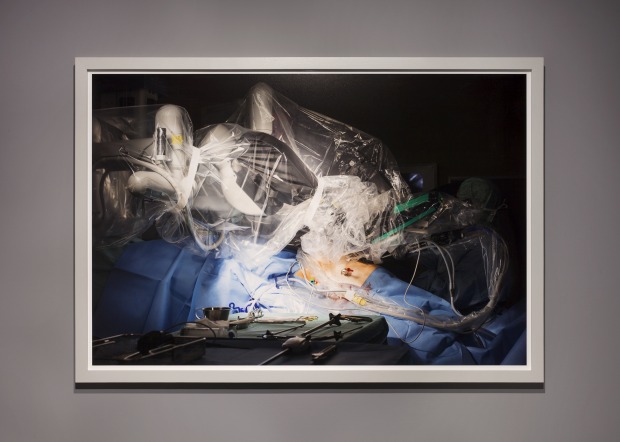

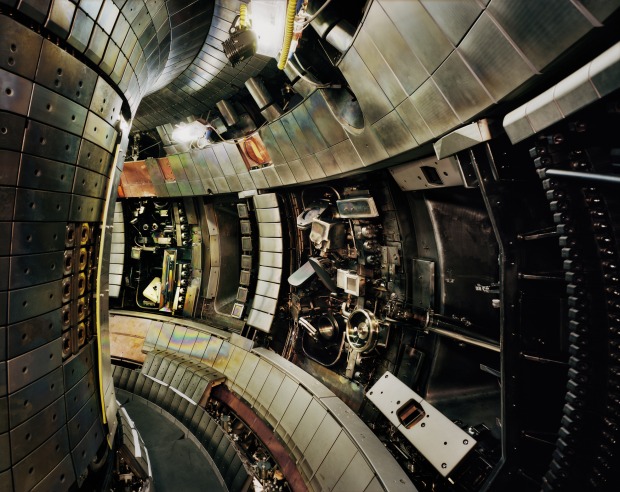

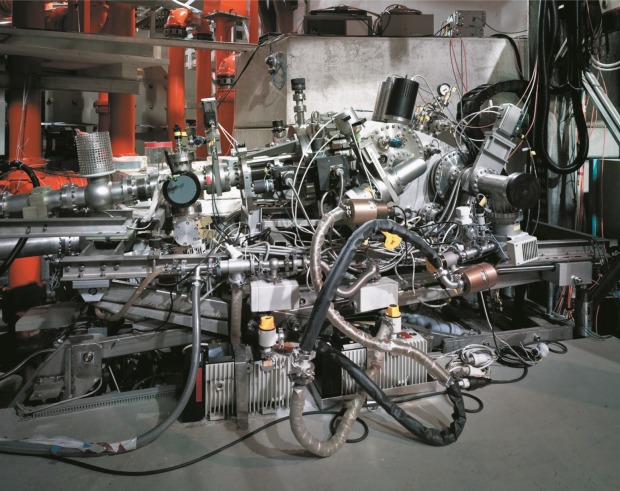

Nature and politics? The first question we must ask ourselves is how these images address the topic. Their sober precision forgoes any effects. What we see is what we see. Places where science and technology are advanced, where research and experimentation take place, where things get tested, examined, measured, monitored and evaluated: laboratories, nature on science’s test bench. A basin with greenish yellow water, with smoke billowing over it, at the University of Edinburgh; a highly complicated measuring system at the Helmholtz-Zentrum in Berlin; a kind of robot workshop at Georgia Tech in Atlanta. Struth’s images show us these situations and the captions point tersely to what it is we are seeing. However, as one swiftly discerns, the initial explanation given by the plain captions, the plausible grounds thus created, do not really get you much further. Which is also why Thomas Struth does not trust captions. What an image means is not grasped simply by knowing what it shows. For Struth is not engaging here in documentary photographs that simply seek to place something in an optimal light and are exhausted in the representation of the factual. The factual, the subject matter, stands for something different.

At the same time, it immediately becomes clear that while we see something, and are given an explanation for it, we do not in so doing in any way understand what is being shown. We view something without grasping it. We take note of references, they possibly give us a rough sense of what is happening at these locations and what all these apparatuses do. Be that as it may, these photographs are never fit for a text book, they never serve the purpose of explaining the configurations presented. Their actual purpose is not to shed light on the “Who”, “When”, “What”, “How”, and “Where”.

On the other hand, these images do not simply present themselves. They do not coquettishly ask what they can or cannot do. In other words, the issue here is not the problems of photographic representation in rendering comprehensible the content shown, or in refusing to do just that. In this case, photography does not refer to itself, either technically or semantically. This leads to a situation where it can superficially be construed as documentation because it serves up readily accessible images, does not create mysteries and eschews special effects. Struth’s images challenge us not only to look very closely, but above all to use our understanding, our approach to reading images, our customary habits of interpreting them and the signification we reflexively attribute to them. One thinks one knows what is supposedly being said to us when these things are shown to us in this way in this given context. Ever since the 19th century, the achievements of scientific civilization have been closely bound up with the history of whether they could be visualized or not. For almost two centuries photography has accompanied the growth of industrial/technological civilization, and in the process has devised a vocabulary of description and a rhetoric of commentary with which we are all deeply familiar. One approach celebrates the scale and sublime nature of human achievement in an elegiac vein. The other approach opts to be purely objective and neutral, provides the filling for brochures, accompanies explanations, and gives homo faber a terse account of its activities. Another angle opts for a critical vein reminiscent of Rousseau as regards accusatory images; it bemoans the loss of originality and naturalness that the technological world inevitably entails. Anyone moving photographically outside these customary rhetorical patterns is left at best with an ironic attitude toward all the highly scientific/technological razzmatazz. By way of escape those photographers who no longer wish to offer any sort of commentary can only grasp and depict what science and technology generate formalistically as the planet’s ornamental trappings.

All these readings, these received wisdoms on how to understand how that which we are shown is meant, are not really applicable to Thomas Struth’s “Nature & Politics”. Because his approach does not assert something, but rather inquires, explores, evaluates. With complete modesty, almost humbly, a simple question is asked – So what is the question?

One quickly sees that in these images the question as to what is nature is the question as to what is technology. These photographs do not focus on technology per se but only address it as it challenges nature, to the extent that technology articulates what humans can achieve when changing and shaping their world by scientific/technological means. Technology therefore revolves around our freedom, our freedom as individuals and as society. Here, “freedom” means the freedom of humans to choose and define how they develop, what their goal is for themselves and for the world in which they live.

How does one arrive at such an understanding of these images? The subject matter: situations where we witness how people carefully dare move out into the open, the free, the unknown, the unproven, and experiment with it. One could also say that these are situations where we test whether and how new environments can be created and situations where opportunities arise. Because in a broader sense, all these images present experimental set-ups. And in the precise definition of an experimental configuration, the question of what it focuses on always entails limitation. By seeking to explore a particular thing, almost everything else gets excluded. In other words, “Nature & Politics” not only asks the question of how humans create their environment anew, but also the question of the extent to which humans, by doing so, always transgress beyond an existing environment, an existing nature, and destroy it. As regards their subject matter, these photographs thus always unite a respectful with a critical approach. As an artist Thomas Struth is essentially interested in the man as an artist, as an artist creating himself, as the only self-Creator (Pico della Mirandola), in man as “a work of an indefinite shape”. Placed in the world as our own creators, we determine, by virtue of our free will, how and where and what we want to be. Human greatness and dignity do not stem from the fact that man is not definable. Instead, they stem from the fact that they have not been defined, from our condition of having nothing of our own but at the same time being able to appropriate everything. Thomas Struth’s works in “Nature & Politics” investigate exactly how humans conquer things beyond the given and defined, how they go beyond established borders, how they form and indeed create the world for themselves, and thus themselves anew. In this context, Struth is especially intrigued by the fact that this does not happen by simply combining the known and the given in a different or new way. Rather it happens in the Creation of Possibilities (we could propose this as a different title for Struth’s body of works). These photographs explore the question of how new possibilities arise – How does one go beyond the boundary where the world ceases and where one should rationally stop and say: Everything else is impossible? All the photographs reach that boundary. And beyond it. But for that to happen someone must first have thought up new possibilities. One does not by chance simply stumble

into the zone beyond the given. In all the situations which Struth shows us, exploring minds were first confronted by the impossible. Human will and its freedom to want to do something (the political) come up against limits, the given, the possible: Nature. But if one wishes for something or thinks something up, and is then forced to say that it is impossible, it runs against nature; if one thinks of a possibility as being impossible, then one has at least thought it, and it has therefore seen the light of day. Perhaps one notices that something is impossible for certain reasons, but by that very act what has been imagined beyond the realm of the possible is given, and so one can now try all the same to realize it. This is as true of a physical experiment as it is of a thought experiment by Walt Disney, who recreated a memory of Europe in the Californian desert which has become a defining reality of the US mindset.

The boundaries of what is in fact possible is not defined by the world of the given, but by our thought and our imaginings. From these, humans develop models. Science needs its models, technology creates models, society’s thinking needs models, culture gives it models, and individuals model their biographies to fit with their own ideas. And because models change, possibilities change. At the beginning there are not real possibilities; the beginning is always a matter of thought possibilities that prove their validity in the attempt to realize them, or do not as the case may be. Such attempts to realize thought possibilities, to test whether they are actually possibilities, is what Thomas Struth’s “Nature & Politics” shows us; that is the subject matter.

It is striking that the actual subject of these activities, the creature that tests, that creates possibilities, that lives freedom – is absent: The images are devoid of humans. We do not see the king, we see the empty throne, something Byzantine art called hetoimasia: “Preparation of the Throne” for the Second Coming of Christ. Instead of the Judge of the World, we see the representation of his throne, ready for his return. Here, too, the images are aniconic. They show us the fantastic, the grand, the threatening and the awful sides to human freedom by showing us the places where the activity happens and by never showing us a single human being.

Asdex Upgrade Interior 2, Max Planck IPP, Garching 2009, 2011, c-print, 141.6 X 176 cm, ed. of 10

Garching, 2010, c-print, 115.1 X 144 cm, ed. of 10

eyck

eyck